Frontline Health Workers—the Key to Maternal and Newborn Health

By Sarah Alexander, Global Alliance to Prevent Prematurity and Stillbirth (GAPPS)

Did you read the recent column by Nicholas Kristof in the New York Times, “The World’s Modern-Day Lepers: Women with Fistulas?”

He shared the story of Marima, an Ethiopian woman who developed an obstetric fistula after days of obstructed labor. The article highlighted the work of Hamlin Fistula Ethiopia, where surgical repair of fistula transforms women’s lives by allowing them to reintegrate into their communities. But, while the shame of fistula can be removed with a surgical repair, the other frequent outcome of obstructed labor—a stillborn child—will be part of a mother’s story forever.

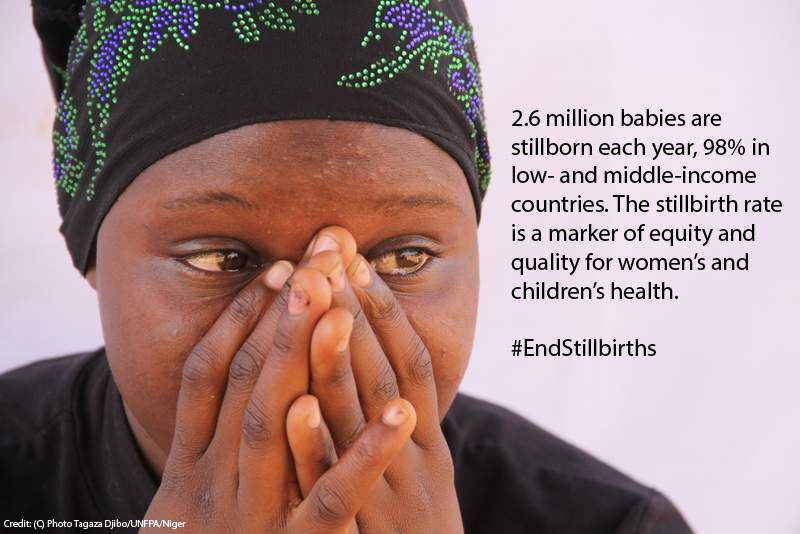

Stillbirth is a major global health issue—and one that is not recognized or discussed despite its magnitude. The 2.6 million annual stillbirths worldwide equal the combined number of deaths from the top three causes of death up to age 5. And since stillbirth does not include a live birth, it is not included in any list of causes of death. Stillbirth is also a global health issue relevant to the developed world. In the United States, about 26,000 stillbirths occur each year—that’s one family left grieving every 21 minutes. However, stillbirths in the developing world are much more prevalent and often look very different from those in the United States.

In developed countries, stillbirth is most frequently associated with placental problems, high blood pressure (preeclampsia), birth defects and more. In the developing world, though, more than 1 million stillbirths per year follow a labor that begins with a fetus alive and ready to be born. In fact, about half of all stillbirths occur during birth, and around three-quarters of those stillbirths are preventable—and they usually are prevented in high-income settings. Preventing those stillbirths depends on frontline health workers.

It’s critical for infections to be treated in pregnant women. For example, in sub-Saharan Africa, malaria is estimated to be associated with about 20 percent of stillbirths and syphilis is associated with 11 percent of stillbirths. Frontline health workers can also address other risk factors including non-communicable diseases, nutrition and lifestyle factors, and fetal growth restriction.

GAPPS, in partnership with Project Concern International and the American College of Nurse-Midwives, is part of a USAID cooperative agreement called Every Preemie – SCALE, which works to provide practical, catalytic, and scalable approaches to expand the uptake of preterm birth and low birth weight interventions in 23 USAID priority countries in Africa and Asia. Many of these activities and interventions have an impact on broader maternal and child health and can help build maternal health programs and advocate for better care of pregnant women before and during labor.

In addition, the recent “Ending Preventable Stillbirths” series in The Lancet builds on strategies to prevent stillbirths and provide better care to women and families following stillbirth. The research shows that 4.2 million women are living with symptoms of depression, stigma and isolation due to stillbirth, and the experiences are shared by women around the world—from Los Angeles to Lusaka.

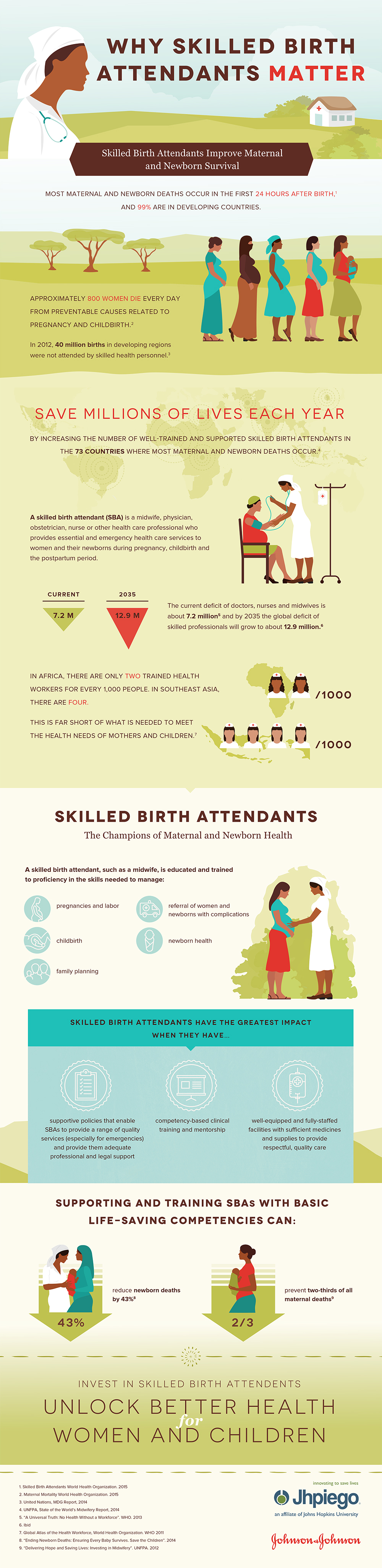

But, most of all, every woman should have a knowledgeable frontline healthcare worker with her during labor and delivery. No woman should continue in labor for days. The obstructed labor that leads to fistula will also result in stillbirth. Having a frontline health worker present is the first and most important step toward making every birth a healthy birth.