The Health Worker Crisis Continues—What Can We Do About It?

In Arusha, Tanzania, a young mother cradles her newborn baby as a nurse administers a pneumococcal vaccine. Photo by: Emily Bartels-Bland for Pathfinder International

Five recommendations to address the global health worker shortage and other challenges.

Despite significant investments in global health workforce development over the past decade, we are still facing a crisis, particularly in places experiencing conflict, epidemics, and climate-driven emergencies. Governments, donors, and global health and development organizations need to take what we’ve learned about strengthening the health workforce and health systems, examine models that have worked, and apply best practices at scale.

While the decimation of health systems in war-torn areas like Gaza and Ukraine has been widely reported and action needs to be taken immediately, in places where Pathfinder works the situation is also critical.

In Burkina Faso, for example, Pathfinder recently made the difficult decision to halt assistance to 20% of the health facilities (50 out of 300) we had been supporting due to continued insecurity. Jihadist groups have hijacked ambulances, looted health facilities, and kidnapped and assaulted health workers. Some health workers have fled to safer places on their own, while the ministry of health has ordered mandatory evacuations of others.

It’s not just countries in conflict. Pakistan and India, with relatively advanced health systems, strong economies, and stable political environments, face health worker shortages, particularly in rural areas. Following population trends in both Pakistan and India, health workers have flocked to cities like Delhi and Karachi, leaving rural areas like Sindh, Pakistan, where child and maternal mortalities far surpass national averages, and more than half of women say they don’t have access to health care.

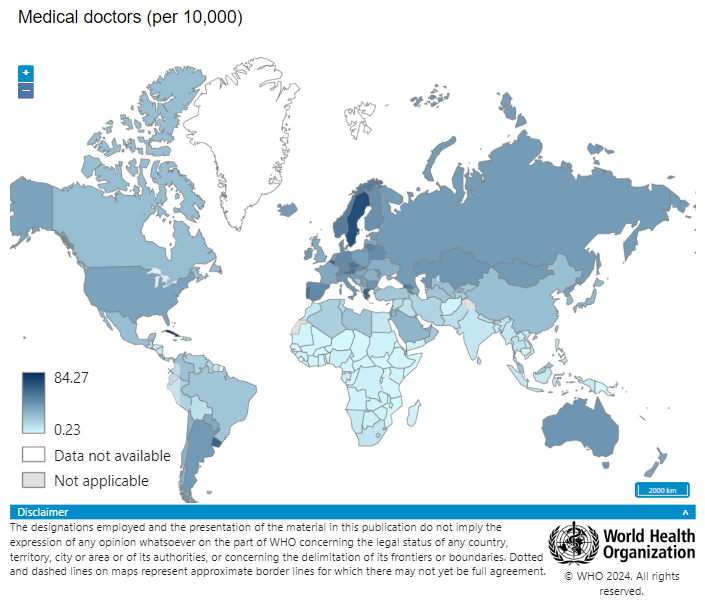

Regions facing the highest burden of disease have the least number of health workers

The World Health Organization still refers to a "global shortage" in human resources for health, estimating there will be a shortfall of more than 10 million health workers by 2030. Regions facing the highest burden of disease have the least number of health workers to deliver essential health services. In the Americas, for example, there are an estimated 82 nursing and midwifery personnel for every 10,000 people, while in the African region, there are only 10 per 10,000. Even in countries where the number of health workers seems sufficient, there are significant disparities between rural and hard-to-reach areas compared to capital cities and urban centers.

Screenshot of the global density of doctors via the World Health Organization's Global Health Observatory.

Across the more than 20 countries in Africa and South Asia where Pathfinder lends support, there are issues with quality of care, where health workers don’t receive adequate training and there is a lack of accreditation and oversight, especially in the private sector. Government investments are sometimes weak, leading to a large proportion of the health workforce that isn’t paid at all, or enough. Health worker safety and protection is often poor, seen clearly during the COVID-19 pandemic, with so many health workers infected.

Where there aren’t enough health workers, or health workers don’t have support and training to meet the requirements of their jobs, people suffer. We see this in our work every day. Children can’t get vaccines. Women can’t get contraception, putting their bodies at risk by enduring multiple unintended pregnancies and giving birth in dangerous conditions. People can’t get lifesaving HIV medicines or treatment for noncommunicable diseases like cancers that are quickly on the rise in many countries.

From our work, here are five recommendations to address the global health worker shortage and other challenges.

1. Replicate or adapt successful community health workforce models.

Deploying a high-performing community health workforce to complement health facilities is integral to delivering quality care, particularly in rural communities. Health Extension Workers in Ethiopia, Accredited Social Health Activists in India, and Lady Health Workers in Pakistan are great examples of how this can work. These community health cadres, seen as trusted and valued members of their communities, are trained to provide specific services and information to communities, and have managers that supervise and mentor them. Importantly, they are paid, considered full-time employees, and on the government payroll. The impact of these models is evident. In Ethiopia, for example, visits from Health Extension Workers are linked to significantly lower risks of child marriage, early pregnancy, and school dropout and a doubling of Ethiopian women using modern contraceptive methods.

2. Make a massive investment in pre-service training.

The quality of health care services depends on the quality of health professionals. Improving the quality of pre-service training in medical schools ensures that students are ready to provide patient-centered health services right after their graduation, reducing the reliance on in-service training. Donors and nongovernmental organizations should support relevant government ministries to improve competency-based training offered by medical training institutions. This requires mapping stakeholders, revising curricula to ensure training materials align with global standards, and equipping training institutions with materials and equipment for simulation and practice. It also requires regularly assessing performance, and using the data collected to inform improvements in training.

3. Address the health worker gender divide.

While women make up 70%of the health workforce, only an estimated 30% are in leadership positions globally. We need to address the gender divide in health care, elevating women to be decision-makers and managers; this is especially important for the advancement of sexual and reproductive health and rights, as well as community health. As frontline caregivers in many communities, women understand health needs and how to deliver care effectively.

4. Increase domestic investments in health worker remuneration, capacity.

To create a sustainable, resilient, and high-performing health workforce, governments need to make serious investments. Health is not only a human right, it is inextricably linked to economic and social well-being, and development. Making investments in health workforce training, and remuneration in particular, as well as systems for collecting and analyzing data that drive decision-making, are the smartest investments.

5. Improve health worker data use for decision-making.

In many places, the COVID-19 pandemic showed us that we can successfully use digital technology for health mentorship, capacity strengthening, and data collection and analysis. We need to leverage technology to support health workers with data collection and analysis, so that they can make timely decisions about the care they provide to clients. Health systems can use the data to inform their investments in human resources for health, including training programs, equipment, and supplies.

Pathfinder continues to push for these solutions through joint advocacy efforts, as a member of the Frontline Health Workers Coalition. Read the Coalition’s advocacy report with additional recommendations: